Responding to Negative Feedback on Your Writing

For most people, writing is a struggle from the outset. The simple act of putting words on a page requires one to dig deeply into the recesses of their mind and bring up something extremely personal.

Being a bad writer doesn’t make you dumb, but it doesn’t paint a good impression. It demonstrates educational prowess and communicative abilities.

When we’re bad at it, people assume things about us that may or may not be fair.

Now that we’ve moved past the midterms, many of you students will be coming face-to-face with an instructor or writing group’s honest assessment of your work. To help you get through it, here are some tips and things to remember should you find yourself experiencing negative feedback.

Let’s get started!

Negative Feedback Tip No. 1: Get psyched.

Whenever you get a paper back from your instructor, or whenever it’s about to go into a peer review group, you know two things will happen for certain:

A. Everyone will love it and have nothing negative to say about it no matter what; or

B. Everyone will hate it and call it the stupidest piece of crap ever written.

In reality, neither of these two extremes are likely to happen. Instead the truth will be somewhere on a spectrum between the two.

Your job is to mentally prepare yourself by considering the worst that could happen and the best that could happen. Not having either of those two things come to pass will prepare you for whatever comments and criticisms come your way.

You’ll be able to better keep your victories in check and your defeats in perspective. That is an important mindset for the road ahead.

Tip No. 2: Overview each comment.

If your instructor is handing you back a graded essay with his comments included, this will be easy. If your peers are throwing comments your way, you may want to record it for dexterity.

Either way, you’re going to get a list of comments. Some of those comments will note minor changes the reviewer feels need to be made. They’re not always right, but you should listen to them.

The same is true when you get positive comments. Consider the source first and the comment second.

If the criticisms highlight major issues with your piece, then you shouldn’t get defensive. Just let it wash over you, and keep a running inventory.

No. 3: Recall points without looking at them.

So you’ve taken inventory of all the negative feedback. What should you do next?

Let’s start with what you shouldn’t do. Don’t jump right back into the comments before taking some time to mentally recall them.

Sit back or in a location that makes it difficult to obsess over the reports. Then, silently, say and summarize each of the criticisms to yourself.

The reason we recommend you do it this way is that it forces you to strip tone and verbiage out of the criticism and get down to the heart of what it was trying to say. In other words, doing it this way will keep you from getting sidetracked and interpreting the attitude behind the comment rather than the substance of it.

Once you can recall the gist of each item, it’s time to address the next point.

No. 4: Reread once the sting has dulled.

There are some hugely beneficial things to doing this the way we’re telling you to do them. Other than cutting out the emotional aspects of negative feedback, it allows you to take your time in digesting the points so that the personal sting dissipates.

It’s all about getting in the right headspace and looking at your own work with a more critical eye. And sometimes criticisms of your work will be misguided, so please don’t take any of this to mean that you’re always wrong.

You’re not always wrong, but you do have to be open to the possibility of being wrong. These steps help get you there.

That being said, once the sting of the negative feedback has dulled, go in with a fresh set of eyes and read the comments word-for-word, asking yourself some questions along the way.

- Why are they saying this?

- Does it make sense?

- Is this substantive or a personal attack?

These questions will force you to be honest with yourself. And that’s the only way you can improve any piece of writing.

No. 5: Reflect.

Reflection time should always be done away from a computer or any kind of distraction. Helpful activities include working out, going for a long walk, and meditation.

Any type of activity that relaxes the mind will be helpful in the processing of criticism. So schedule some time for reflection, and don’t let anyone make you feel guilty about it because it doesn’t “look like you’re working.”

Much of the important work that gets done from a creative perspective gets done when you aren’t going through the motions. Make sure you leave enough time throughout the semester to constructively reflect on assignments and papers and projects where you may have gotten it wrong.

No. 6: Ask yourself how you can make it better.

During your reflective time, it is important to embrace honesty. No one can judge whether you’re being honest with yourself but you, and if you’re not, it will show up in the results.

Don’t learn this lesson the hard way. Really drill down into what critics are saying. View it through their lens if possible. Act like you’re them, and you’re making that same criticism.

Where does it come from? Empathy will take you a long way here, so get into the role-play. When you really give yourself over to it, you may even come up with ways to improve your work that the critics never mentioned.

No. 7: Schedule an appointment with your instructor.

One thing you always want to do in speaking with your professor/instructor, particularly when they’re the ones making the criticisms, is to be respectful of their time and opinions.

While you may not agree with your teacher on every little thing, you should realize their training and knowledge has value to it. They also have to go through the same motions with their other students, and most of the time, they’ll be in the right.

So when you approach an instructor to talk about negative criticisms, you should try to empathize with where he is. Most of the essays that he reads will be subpar, terrible, or at least problematic. His experience reading and reviewing dozens of written projects trains him to look for certain problems more than others.

That means while he may be wrong on one or two things, there likely will be substance behind most of the points. And it’s his goal to make you better, not fail you.

Do be prepared to state your case and the reason you made certain decisions as well as why you think your position works better. But do it in a calm and cordial manner. You may change his mind; you may not. But you’ll certainly earn his respect.

No. 8: Go back through and make changes.

Many common criticisms that instructors make of their students’ work include plagiarism, bad grammar, and poor syntax.

If you can tackle these three things, you’ll already be ahead of most of your classmates. When you go back through to make changes like these, remember that mistakes like plagiarism aren’t always made on purpose, so it pays to be methodical and focused as you’re making another pass on the draft.

Plagiarism to expand word count is a common theme, wherein writers will directly quote too much text from another source. Even when you give credit, this can constitute as plagiarism because you’re lifting someone else’s ideas entirely for the purpose of supporting your own original work.

And if this isn’t considered a form of plagiarism, it’s certainly lazy. As a result, you’re likely to get called on the carpet, so don’t do it.

As for grammar and syntax, consider programs like Hemingway App or Grammarly, which make editing for misspellings, mis-punctuations, readability, and other factors so much easier to manage.

No. 9: Leave enough time to avoid the rush.

Time is definitely a factor for students with full-time schedules, so you will not have a minute to waste when it comes to addressing problems with your essays or writing projects and getting them submitted in a timely manner.

You have to remember that all outside help you receive from your teacher, teacher’s assistant, or tutor will have to be worked in around their schedule. They may have other people they’re helping, too, so plan for that.

The important thing is that you manage your time effectively enough to address the major structural problems with your work should they exist.

By leaving yourself enough time to seek outside help, make necessary corrections, and rewrite portions of the paper (if needed), you’ll be able to keep a social life, stay above board in other classes, and turn in a better paper without rushing the process.

And before you say something like, “I work better under pressure,” just remember that you thought that way before turning in the first draft, too.

No. 10: Read the ‘final’ draft out loud.

Turning in a final draft should not happen before you’ve given yourself one last chance to dig deeply into the words of the paper itself. The best way to do that is to use your voice.

Literally.

Go someplace private with no noises or distractions. Start with the first word of the first paragraph. In your best Morgan Freeman voice, belt out the next 5-10 pages — however long the finished piece is — making notes of what works and what doesn’t along the way.

We know it’s a digital society and all, but you should consider doing this from a hard copy with a red ink pen in hand to make any notes whenever and wherever you stumble. Then, take the marked-up copy back to your word processor and input the final changes.

The act of reading aloud forces you to mutter what actually is on the page instead of what you think is on the page. When we read silently, we have a tendency to give ourselves the benefit of the doubt and read what we meant instead of what we wrote.

Be hard on yourself.

No. 11: Connect with the instructor once more after changes are made.

If there is still time in the semester and your instructor’s schedule allows it, meet back with her to discuss the changes you made and get any input or advice before the due date.

This meeting is helpful in a number of ways, but the most important is that it can help you feel confident about the direction you’re going or highlight other problems that may exist with the essay.

Either way, you will have the tools and the confidence you need to make a final push before it’s too late.

No. 12: Write a short ‘thank you’ message.

This may seem annoying, and who knows, maybe it is. But it’s always seemed to work on my end. Whenever I turned in finished essays like these — to recap: gone through peer reviews, edit requests made, edits implemented — I always like to include a thank-you note to the instructor.

This is not a suck-up device though it may seem that way on the surface.

No, the purpose of the thank-you note is to show the instructor that yes, you did appreciate her time and advice, but it’s also to say, “These are the changes we talked about. These are the changes that were made. My paper should be awesome now because it has incorporated all or most of what you told me to do.”

Unfortunately, I’ve found that people in the position of criticizing others’ work can forget what they’ve told you from time to time. They can be incredibly inconsistent, in other words, so if they come at you on the final grade with a new set of previously unmentioned demands, that’s not fair to you.

The thank-you note/summary method is my way of telling them, “I listened. I took it to heart. I did what you told me. If you don’t like it at this point, it’s all on you, buddy. I’m watching you.”

Call it a subtle form of intimidation if you want, but it usually protects you from the unfairness of having the rules changed on you that late in the game.

No. 13: Accept the outcome gracefully.

No matter what you do, the final decision is not yours to make at the end of the day. Your essay will either live or die by the assessment. Sometimes these things end unfairly, but if you stick to the other advice we’ve mentioned above, the likelihood is less.

When you do get the essay back, accept that there are outcomes you can’t control and the best thing to do is to move forward.

In closing

As you move further into the semester, don’t delay. Writing projects take a lot of work to do right, and you need to leave enough time to address every issue that needs to be addressed.

At the same time, don’t feel badly if your first or subsequent drafts have issues. The goal, again, is to make you a better writer and a better communicator. Keep that as your focus instead of allowing negative feedback to destroy your confidence.

What are some of the most painful pieces of advice you’ve ever received? How did you handle it? Share your experiences, as well as any questions you may have, in the comments section below.

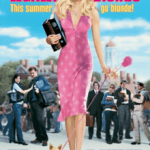

[Featured Image by Monster.com]