5 GED Writing Tips To Help You Succeed

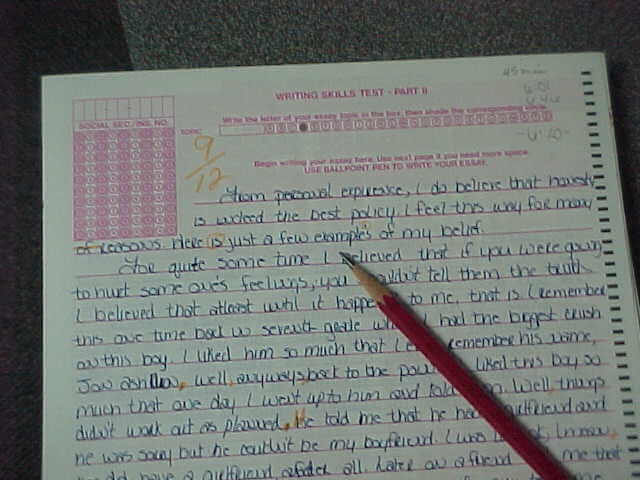

There is no knowledge base or word bank that you can look over and magically come out prepared. Becoming a great writer is essentially a years-long process. Unfortunately, you don’t have that long before the next exam. But luckily, you don’t have to be a great writer to pass the writing portion of the exam. All you need to be is competent. That means:

- Stating a thesis

- Supporting your thesis with examples

- Communicating ideas clearly and effectively

- Showing an understanding for the basic rules of spelling, grammar, and syntax

You don’t have to be perfect, but you do need to be able to answer the question in essay form. To help, we’ve put together these five GED writing tips that should set you on your way.

First, Ditch The Texting Speech.

It’s common sense that an essay question is not a text message. So don’t treat it like one! Typing “u” for “you” or “ur” for “your” and “you’re” is something that happens far too often in classroom compositions, and that can carry over into testing. It isn’t that people who make this mistake are stupid. They’re just so used to sending text messages that a lot of those poor shorthand habits seep in to formal writing. The best thing that you can do to make sure this doesn’t find its way into your work is to identify your shorthand go-to’s ahead of time. If you know that you have a tendency to shorten words or sub them out with letters (like “u”), then make sure you watch for those types of words when doing a final proof of your written response before submitting. It’s a lot easier to spot individual mixups when you’re seeking them out specifically. So do a run through the text where these types of words are all that you’re looking for.

Secondly, Mind Your Homonyms.

One of the worst pieces of advice that you’ll ever hear regarding the English language is to spell things like they sound. Big mistake. And homonyms bear a great deal of the blame. Combinations like “you’re, your, yore,” “bear, bare,” and “their, they’re, there” are often used incorrectly. Page through any 500-page study guide, and you’ll see a few pages devoted entirely to existing homonyms in the English language. Here’s a pretty comprehensive list if you want to see more.

If you have trouble distinguishing the rules, it can’t hurt to give these another look in your textbook or consult with your teacher to see if she has any suggestions for how to remember certain homonyms. It’s impossible to go down the list above and learn all of them, especially in such a short period of time, but you can make great headway if you start targeting this specific language function now.

Thirdly, Make Proofreading A Priority.

Proofreading sounds so boring, especially if you’re not in love with regular reading. However, it is essential when it comes to catching mistakes. When you’re in a crunch to write an entire essay in a short amount of time, mistakes are going to happen, and the more of them you catch the better! Unfortunately, when you read something as an editor the same way that you do as a writer, you tend to see what you want to see instead of what’s actually there on the page.

One good tip we’ve picked up over the years that has helped us shift gears to editorial is this: Start with the last sentence you wrote and read back through to the beginning, one sentence at a time. This forces your eyes to slow down and see the words for what they are on the page, rather than what they are in your head.

Fourthly, Be Formal.

Just as important as being able to communicate ideas, is demonstrating that you have a command of the English language — at least enough where you can distinguish the forms of writing and place them in the right connotation. By using formal English instead of slang, you’re able to show that you recognize what the question is calling for, and that you’re able to fashion the appropriate response.

Formal No: “I gave him forty bucks to wash and detail my car, and he came back with it looking squeaky clean from the inside, out.

Formal Yes: “The service charged forty dollars for its full-service package, which included a car wash and interior detail.”

Word choice, ladies and gentlemen. It’s not just about what you say, but how you say it.

Finally, Stay Structured.

GED written response questions want more than random facts and opinions strung together to fill out a word or paragraph count. They want you to take a look at the questions, analyze it, and then present that analysis as a series of carefully worded sentences that support your main idea. To pull off that little miracle in the time allotted, you’ll need to embrace structure.

While the word itself sounds boring, it will free your mind to be creative, thought-provoking, and focused. One of the most common forms of structure used at the high school level is that of the five-paragraph essay.

In the first paragraph, the writer sets up the topic and issues a thesis statement or main idea, which will tie in to every subsequent sub-topic presented in the body.

The second, third, and fourth paragraphs, each tackle a main point that ties back in to the thesis statement and works to support the whole. Each new paragraph ends with a transition leading into the next until you get to the end of the fourth paragraph. From there, you transition to your concluding paragraph where you restate the thesis and facts that support it and leave your reader with a final statement that encourages the reader in some way — to seek answers, to think for themselves, to remember something fondly. This varies depending on the topic of the essay and how it is written leading up to that point.

Once you look beyond the length of the piece and realize that each of the middle paragraphs are set up largely in the same way, and that the introductory and conclusion paragraphs have their own functions, it becomes easier to think less about what you’re going to write and more about how you’re going to say it.

In Summary

The writing portion is a good indication of your thoughtfulness as a student and your ability to recognize personal and professional situations and respond accordingly. While it may not kill your chances of performing well on the GED, it’s worth noting that students struggling with this portion of the test will probably struggle in other areas. If you feel uneasy about your chances, we suggest doing as much writing as possible before exam day.

Recreate the environment of the test. Use actual practice questions to get a sense for the types of questions asked. And while you’re at it, keep reading. After all, good writers always start out as readers, and they continue to do so throughout the entirety of their careers. Best of luck as you move forward with the GED writing test.

Where can I write a eassy online and get grader on before I take my GED because I have problems writing my easy and before I take it I would like to write one and see how I do